Apple’s Long Journey to the M1 Pro Chip

This twitter thread explores the journey from the original Mac to today’s M1 Pro-based MacBook and the history behind such a mind-blowing innovation.

Apple’s M1 Pro/Max is the second step in a major change in computing. What might be seen as an evolution from iPhone/ARM is really part of an Apple story that began in 1991 with PowerPC. And what a story of innovation 💡 1/ [Quick thoughts]

2/ If you studied Computer Science in the 80s then you were deep into the raging debate of RISC v. CISC. And what a debate it was. Out of that debate emerged an implementation at IBM, the POWER processor/instruction set. And an SV company MIPS.

3/ PowerPC was a huge investment from IBM — an effort to regain end-to-end control of computing, starting with workstations. They had no software platform really (though Unix was all the rage for workstations and OS/2 all the hope) so the big bet was on Windows NT.

4/ An unlikely partnership was formed between IBM, Apple, Microsoft. This followed the breakup of the alliance known as AIM between Apple, IBM, and Motorola. Recall, Moto was the provider for all Apple’s chips going back to the start of Macintosh.

5/ Apple relied on Motorola including the launch of the PowerBook. But even in the latest 68030 Mac was woefully far behind Intel PCs. While the 68030 was a fantastic chip, Mac software didn’t fully exploit it and WinTel was iterating rapidly to the 486 [6 months later than ‘030 Macs and was significantly more powerful]. Many at Apple, such as @gassee firmly believed Apple needed to gain full control of computing, but becoming a Chip maker cost billions.

6/ This is really key in terms of understanding the present. Apple was essentially left hanging by a partner for chips, when their core deliverable to customers was a computer. That seemed an impossible situation.

7/ Over in x86 land, compute speeds and megahertz kept rising with Moore’s Law. Intel’s investment and excellence in manufacturing made it all but impossible for anyone to catch up, especially making a similar CISC product.

8/ Apple moving to x86 would put them in direct competition with everyone else. That seemed the opposite of the right way to go, much as licensing Macintosh System seems to be wrong.

9/ This led to a bet on PowerPC and the release of the first Power Macintosh 6100 in *March 1994*. The project was a very bumpy ride with IBM but also an enormously difficult software project.

10/ The Mac System needed to be ported to the PowerPC chipset, including all the hardware and peripherals. It also meant the whole ecosystem needed to move as well, but that ecosystem wasn’t healthy and had started to slow down Mac and favor Windows.

11/ To ease transition, power of PowerPC was used for 68k emulation. This allowed lagging apps (Photoshop, which took something like 2 years to release as a native app) to at least run on new hardware, but performance was marginal at best. BUT Apple learned a great deal in this transition — tooling (like Universal), emulation, and compilers.

12/ The results were lukewarm when it came to performance, especially versus x86. In the meantime, developers were investing heavily in x86 and Intel was investing billions in scale. The gap at launch would get worse, not better over time.

13/ There was little Apple could do for the next few years. Essentially the price/performance gap would continue to become even more bleak. Then Steve Jobs returned.

14/ Of course first came the most famous PowerPC Macintosh of all time. By focusing on consumers and the internet, the weakness of PowerPC could be ignored. The industrial design was a hit too. The G3 then G4.

15/ In the meantime, Apple began to use ARM processors for the iPod. ARM was a RISC design, but had only achieved success in small devices and peripherals. Intel and many other companies were all ARM architecture licensees. This is how Apple got into chips. No one worried.

Note I should have mentioned the Newton here as it was clearly the first ARM device from Apple, though it was another generation of people and from what I gather there was not a lot of continuity when it got to iPod unlike the OS evolution.

16/ The end-to-end control of iPod was exactly what was needed to bring together hardware, software, and internet services. First some custom chip features, then more, then more…Of course as we know now, that also marked the resurgence of Apple.

17/ Rebuilding Macintosh began as well. By this time NeXTStep was already ported to Intel. The work to get the rest of Mac working involved a lot of knowledge about chipset transitions from NeXT and Apple history. Note: Many senior Apple engineers worked at NeXT, and several of them worked at Apple previously.

18/ There were no choices for chipsets for “computers” at the time, but of course Apple was clearly going to use ARM for the iPhone (and iPad) project which itself has a long and interesting story (out of context here).

18.1/ Was asked: Apple using Intel for phones, how Intel famously declined. I’ve heard first-hand from both sides and honestly not sure how serious Apple was or how uncommitted Intel was. Also, within Apple it was a debate of sorts, which seems crazy given what I saw on Windows.

19/ At the 2005 WWDC, jobs announced that Apple would be transitioning to Intel. Many said this is something that should have happened long ago. It really was the only option (IBM was not going to invest “Intel money”)

20/ So while the phone was going on and ultimately released on ARM in 2007, the first Intel Mac was released in January 2006. That was essentially a PowerBook but with Intel inside. If this looks familiar it is because that’s exactly how Apple did the M1. This is a huge learning point — the DTK 2.0 (the first one was for the transition to x86) was essentially an iPhone inside a Mac Mini chassis. It was proof of concept. Then later the first MacBook Air and MacBook Pro with M1 were also chassis look-alikes.

21/ In 2008, proving it could innovate and even do with with Intel, Apple introduced the MacBook Air. It was the first laptop on a new Intel chipset (though everyone would eventually have this for Windows, no one built a MacBook Air-like PC). Until Ultrabooks there was no PC.

22/ A huge part of the Intel transition was bringing up hardware, seeding developers, universal binary, and emulating PPC instructions. If this all sounds familiar it is because it is 2.0 of a process that was done in the 68k->PPC transition. It was much smoother. Same process, just iterated. And apps came on board as native much faster. Photoshop, Office, etc. all came much sooner.

23/ As Apple progressed with ARM it became clear that the breadth of the ecosystem was a benefit for ARM but was holding Apple back in terms of innovating. iPhone success gave Apple the resources to realize its chipset dream. Thus the System on Chip from Apple began.

Note. In 2009 Apple acquired PA Semiconductor. I should have included this because it was a huge step, though many at the time were quite puzzled by it. This story below shows how confused most were. Apple of course was not.

24/ The M1 chip was a realization of all the iPad and iPhone work (sensors, OS port, security, power management, graphics, and more).

The M1 not only aimed at fixing what ailed Intel, but also PPC. It was learning from the past decade+.

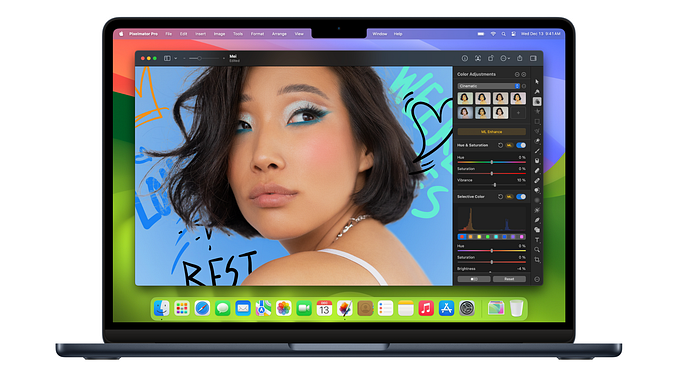

25/ When you look at M1 Pro/Max today it is tempting to think of this in terms of performance, but performance per watt AND integrated graphics AND integrated memory AND integrated application processors is innovation in an entirely different direction. Just the beginning.

26/ Here’s a thing about “Laptops versus Phones”. The Phone is the computer for everyone around the world now. Laptops (and desktops) are specialized devices for work. About 400M people really use/need laptops for work. That’s what M1 is for and why Apple does not need to stress about pricing like it did in the 1990s — essential tools for highly paid information workers are worth the money.

27/ The number of laptops won’t grow, but it is likely Apple will continue to take share from Windows (as will Chromebooks). At 275M units a year, laptops are big but serving this base of 400M. Phones serve everyone including them. That’s where software innovation is for masses.

28/ That’s why this transition to M1 is so fascinating. Back when Apple went on its own with the A-series chips, one could easily be concerned that they would end up in the same place as PPC — not enough volume to win against Qualcomm/Samsung doing their ARM designs.

29/ Apple, by virtue of being vertically integrated, raced ahead. Because of their units and revenue/R&D investment they are in a globally unique perspective. Today, Qualcomm is closer to Intel than it is to Apple Si/Ax/Mx.

30/ Even though Intel serves Windows, ARM/QC/Sam serve Android, they all must serve myriad of OEMs. It appears as though that point of openness (v say at the s/w and service level) is a real constraint on innovation. Partners don’t all want to make the same device, for example.

31/ At the same time, Apple itself has developed a whole family of operating systems. These are not just related, but vastly similar enabling a huge ecosystem opportunity. THIS was Microsoft’s vision going back to early 1990s. Slide from 1992 PDC.

31.1/ This is the slide that goes with 31 that was left out/ The Microsoft history of Scalable Windows. This is the first slide from 1992 PDC. Over the next few years it would grow at the low end (Windows CE, Wallet) and high end (High Performance Computing w/NT and Itanium [sic]).

32/ The M1x capabilities of shared memory, SoC that isn’t just smaller but has so many aux functions, Pro Res, super fast SSD, even multiple TB ports — all these things require deeply integrated software (from the chipset to the experience).

33/ Some might say only 1% of people (of the 400M) even need these. 2 things.

- First, everything today for super advanced becomes commonplace down the road.

- Second, never before has one desireable brand made the ubiquitous device AND the super high end one.

34/ Across phone, tablet, tv, watch, speaker, laptop, desktop, there’s a platform of capabilities are unmatched even in one device group, let alone the whole spectrum. It would be like if Ferrari also made mass market passenger cars and electric bikes. Unprecedented situation.

35/ I’d be remiss if I didn’t say these weren’t perfect devices. Why no ethernet in the giant power brick like iMac? Why no cellular option? Yeah FaceID doesn’t fit but soon? Oh and people harping about the notch, STOP!

PS/ This thread is about context, not the whole story. There are a lot more details, even books, about this particular transition. Here’s a deep overview of PowerPC to show what apple was after, and challenges.

PPS/ Windows NT spent a huge amount of effort on PowerPC (including even young me porting Microsoft Foundation Classes). Alas, no hardware ever showed up. BUT that worked is what made porting NT to ARM some good learning.

PPPS/ Pay attention to how Apple share of regular PCs is growing, keeping in mind they also have growing phones and all tablets and most watches. Pretty interesting share change.